Unmasking White Preaching with Dr. Andrew Wymer

February 23, 2024

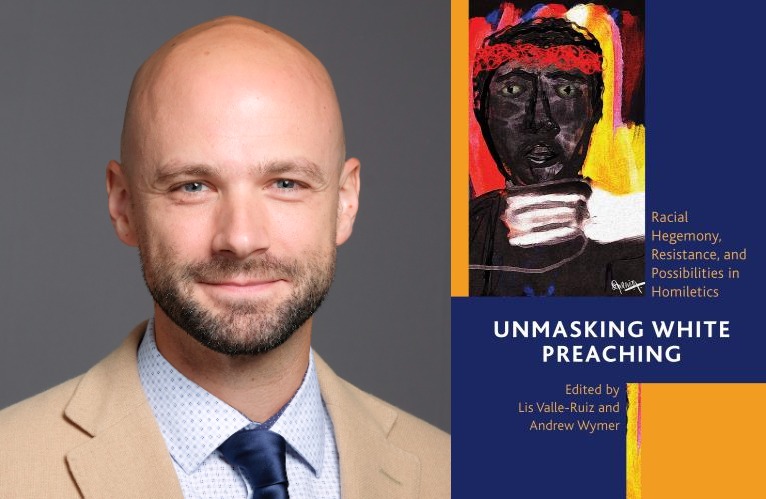

Professor Andrew Wymer is Garrett-Evangelical’s recently promoted and tenured associate professor of preaching and worship. To celebrate his appointment, I sat down with him to talk about the book he co-edited: Unmasking White Preaching: Racial Hegemony, Resistance, and Possibilities in Homiletics, now available to pre-order in paperback. He shared how he’s excited to see his scholarship “align with community advocacy work and tangible efforts to pursue equity in Evanston and beyond.” One initiative for which he’s particularly excited is research with Reverend Dr. Michael Woolf, senior minister at Lake Street Church in Evanston. They are investigating the role of faith communities in reparations efforts. “By better understanding the role of faith,” he explains, “hopefully we can bolster other municipal efforts for reparations and eventual statewide or national reparations.” That same focus on disrupting unjust systems sits at the heart of his book.

Benjamin Perry (BP):

In your book Unmasking White Preaching, you describe how whiteness sets the norm for how we evaluate homiletics. How is what we consider “good preaching” racialized?

Andrew Wymer (AW):

We all have so many implicit assumptions about preaching that we don’t think about critically. They’re always operating. We trust our thinking, “Oh, we’ll recognize good preaching when we see it.” But the reality is, our evaluations of both others and us are formed by centuries-old systems of power. The book invites us to look anew and ask: “How do we move forward now recognizing this? How do we start to disrupt it in the preaching moment and throughout our communities?”

BP: So, what are some ways that whiteness shapes our normativities?

AW: One of the first things I ask some of my introductory preaching classes to do is: Close your eyes and imagine the voice of God. God is speaking to you. Who just spoke? What voice did they use? Too frequently, it’s a male, very deep voice of European descent. So, instantly we know that our perceptions of God are often formed along lines of patriarchy and race, and the assumptions we have about who God is are too often shaped by whiteness.

The book collects many different perspectives and insights from people from different social locations and invites us to consider a number of ways that whiteness has restricted our awareness of how we can interact with God in preaching and liturgical moments, as well as strategies to begin to disrupt that.

BP: When those forces aren’t checked, how does this affect non-white people who enter the pulpit?

AW: It starts with who gets to go in the pulpit. There’s significant racially minoritized scholarship naming how whiteness and maleness limit and shape access to the pulpit itself. That’s literal and metaphorical—it can include access to ordination and to non-pulpit preaching spaces. Who is and who is not given a church? Who has to do pulpit supply to be able to live out their preaching vocation? Who has to preach outside of the pulpit because the pulpit itself is restricted by gender, sexuality, and race?

BP: Once folks get into the pulpit, how do normativities of whiteness limit non-white preachers?

AW: To give one example: There’s an array of Black homileticians over the past decades who name how Black students desiring a theological degree have often had to go to historically white institutions where they learn from professors who likely have had no formation in and little critical awareness of Black preaching traditions. So, there’s a double consciousness that is necessary to survive. To succeed, they must learn to preach white, but to be who they are with integrity and to go back to their faith community and preach in their own tradition, they must cultivate authenticity. That double consciousness is in itself an expression of violence.

BP: What parts of working on the book still resonate in your mind?

AW: The process of putting the book together is something I’m still sitting with. In its own way, the book required a process of contesting, navigating, addressing the very ways in which the editors and the contributors are located within racial systems and other intersecting forms of oppression. The white contributors and editor, in particular, brought that bias with us and had to navigate disrupting that inside of ourselves as well as in our field alongside our colleagues of color who already carried the burden of working from racially minoritized social locations to this task of disrupting it in our discipline.

BP: What are some of the things that you hope people who read the book will take away?

AW: I hope people first critically attend to white racial formations and identities and recognize how those are operative in our world—particularly for those of us who are formed into white racial identities and privileges. But I hope people also realize that there’s so much in homiletics that’s more interesting and captivating than whiteness. People should take whiteness seriously but move beyond a focus on whiteness to the brilliance and possibility that’s brought to us through non-dominant perspectives—the brilliant scholars in this book who invite us into a different way of thinking about preaching and being in the world.

BP: Thank you for saying that because it struck me that even centering conversation around deconstructing whiteness is still, in some ways, a function of centering whiteness. What are some of the more pressing questions in your mind when it as it relates to preaching?

AW: One of the pressing questions that emerges for me is how to attend to racism and race in ways that grapple with the diversity and fluidity with which these things change. Racialization is so complex, and it’s easy to slip into binaries. Not just a Black/white binary that’s exclusive of others, but it’s also easy to slip into a focus that doesn’t account for the variety of racialization beyond the United States.

Another question interrogates the form and structure of preaching—one manifestation of which is in sermon styles. A lot of our traditions are profoundly shaped by European, dominant, theological, and ecclesial traditions. Are the accompanying homiletic forms themselves corrupted because they emerge out of a tradition that was complicit in colonialism? Can those structures, in any way, be retrieved and reapplied in liberative ways? And am I willing to learn new structures, to experiment in ways that my culture and theological traditions have shaped me to be uncomfortable with?

BP: I love that you name comfort here as a salient factor. What is the relationship between discomfort and faith formation?

AW: For those of us from privileged social locations, the systems that shape our society are situated to try and make us more comfortable–not just comfortable in an emotional sense, but comfortable economically, politically, and culturally. The pathway to equity and to justice is going to require discomfort on the part of the privileged. A liberating faith is going to be a faith that constantly requires us folk of privilege to navigate discomfort.

For people called to be ministers, there’s a level of savviness needed to help people and communities of privilege navigate discomfort, leading them on a liberating path that will disrupt these very selectively applied social comforts that have caused sustained violence to racially minoritized persons and communities for centuries.

BP: Last question: To normalize white preaching circumscribes God inside of a small, particular place. If we can disrupt that, what does the diversity ways that people talk about God in the preaching moment say about God?

AW: I’m very deeply impacted by liberation theology, by images of a non-dominant God who is present with marginalized communities and persons. The artwork on the front of the book is actually a deeply troubling image emerging from a liberation perspective. It is a Black Christ being choked by a white hand. This book seeks to disrupt that violence and to recognize God’s presence in and preferential care for racially minoritized persons and communities. The book considers how preachers can disrupt that violence in a number of different ways. Even the use of sermon structures from a different context can help us see more of God’s fullness. The authors in this book try to help us reckon with ways of preaching that invite the possibility of a God who is beyond our knowing and control. Ultimately, white Jesus is idolatrous and demonic—an attempt to capture and elevate a very particular image of Christ that reflects and supports a brutal system of power. I believe in a God who can’t be accurately captured in one image and who can be encountered at the margins of society. Hopefully, this book will help create space to encounter that God.